By John L. Trotti

South Carolina’s modern juvenile justice system now incorporates a broad array of services to protect the public, prevent delinquency, and treat and rehabilitate juvenile offenders. That is a far cry from its beginnings, almost 130 years ago.

Before the 19th century in America, the modern concept of “juvenile justice” did not exist. Little distinction was made in the justice system between adults and juveniles. In practice, delinquent juveniles might be apprenticed or “binded out” to local craftsman or responsible adults. They might also be punished by their church, parents, or community with public floggings or other, even harsher, forms of punishment.

By the mid-19th century, many states were beginning to make a distinction between juvenile and adult offenders in the criminal justice system. In 1825, the first juvenile “House of Refuge” was established in New York by the Society for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency. Conditions in these houses were often harsh, with children used as little more than slave labor. But, nevertheless, they represented the first recognition that children require special treatment in the criminal justice system.

After the Civil War, the “Houses of Refuge” were replaced by larger state and city sponsored “Reform Schools,” “Industrial Schools,” and “Training Schools.” South Carolina began its first statewide juvenile justice effort in 1893, when a wing of the state penitentiary was set aside as a “reformatory” for delinquent boys.

By the turn of the century, Progressive Era reformers in the United States began to turn their attention to juvenile justice—taking a more paternalistic attitude towards juveniles and crime. These reformers pioneered the concept of parens patriae or “The State as Parent.” Parens patriae advocates argued that the state had an obligation to not only act in the public interest when dealing with juvenile crime, but also to serve the best interest of the child involved.

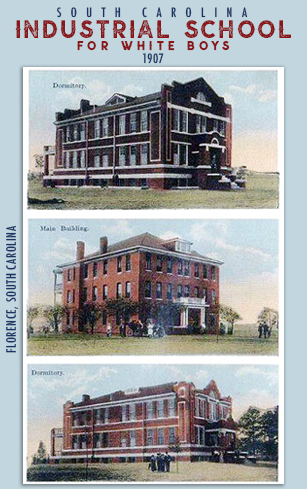

In 1906 the General Assembly established a segregated industrial school system for boys in the state. In 1907, the Reformatory for Negro boys was built on what would later become the Department of Juvenile Justice’s Shivers Road facility. And the Industrial School for White Boys was built in Florence that same year. In 1918, the State purchased additional land on what would later become DJJ’s Broad River Road Complex to establish the Industrial School for (white) Girls, the first juvenile justice facility for girls in South Carolina.

In 1946, legislation was enacted which placed these industrial school facilities under the Board of State Industrial Schools. In 1954, a Division of Placement and Aftercare was created, empowered to release incarcerated children prior to their twenty-first birthday.

During this period, state funds were used primarily for physical improvements in the institutions, with no resources for recruiting professional staff. Hence the institutions were mainly punitive with little emphasis on treatment and rehabilitation. Reforms did not come about until the late 1960s.

In 1966 the name of the governing body was changed to the Board of Juvenile Corrections and the following year a state Director was named. The new Director was unified and desegregated the three institutions, but his office was provided no staff. It was not until 1968, in the aftermath of a class-action lawsuit, that the court ordered compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This freed up federal funding through the Elementary and Secondary Schools Act, which engendered major improvements in academic and vocational instruction.

An entirely new agency was created in 1969. The Department of Juvenile Corrections came into being with a separate Division of Placement and Aftercare. Professional staff were charged with developing and implementing community programs, resulting in a drop in institutional population.

In 1972, the Department of Juvenile Corrections became the Department of Youth Services with two internal divisions: Juvenile Corrections, which was responsible for treating institutionalized children, and the Youth Bureau, charged with implementing community programs. A major focus of the Youth Bureau was the de-institutionalization of status offenders. Status offenses are charges such as truancy and running away, which are not crimes for the adult population.

The Judicial Reform Act followed in 1976. This legislation expanded the network of individual county Family Courts into a unified system operated by the state. The act was amended in 1978 to provide that the Department of Juvenile Placement and Aftercare (JP&A) administer juvenile intake and probation.

In 1980 JP&A was given the additional responsibility of detention/release screening for juveniles who were taken into custody by law enforcement.

Even though substantial progress was realized in the eleven year period leading up to 1980, it became apparent that the juvenile justice system had evolved into two separate agencies resulting in costly duplication, particularly in the areas of community programs and administration. Recognizing this, the Legislature passed the Youth Services Act of 1981, merging Juvenile Placement and Aftercare and Youth Services into a single Department of Youth Services.

The enabling legislation cited the following organizational and programmatic needs: 1) developing a single policy direction for juvenile justice in South Carolina; 2) offering a comprehensive array of community-based treatment and prevention programs; 3) combining management and support functions to avoid duplication, freeing resources for enhanced services; 4) eliminating competition for funding inherent in a two-agency system; 5) presenting a consistent and comprehensive system of juvenile justice services. The Youth Services Act created a Policy Board to guide the agency (a Board which was dissolved during restructuring in 1993) and a separate and independent Juvenile Parole Board to determine the time of release for institutionalized juveniles.

The 1981 legislation also changed several major portions of the juvenile code. It prohibited commitment of status offenders to the secure facilities except for evaluation and increased the minimum age for institutionalization of all other offenders from 10 to 12. It also established new mandates for local jail detention of juveniles, requiring court orders for 11- and 12-year-olds and prohibiting such confinement for juveniles under the age of 11.

In 1993, the Department of Youth Services was renamed and reorganized as part of the government restructuring initiative. On July 1, 1993, it became known as the South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice, cabinet-level agency. The Director is now appointed by the Governor with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Also on July 1, 1993, legislation went into effect which prohibited the confinement of children for more than six hours “in a place of detention for adults,’’ specified criteria for the detention of youth in secure juvenile facilities and required a court hearing within 24 hours of a juvenile being taken into custody. These were major steps forward, ending years of non-compliance with federal mandates and accepted practices in the handling of delinquent juveniles.

In 2007, legislation went into effect allowing DJJ to establish its own internal release authority—for release of incarcerated offenders with less serious offenses, such as misdemeanors and probation violations.